Screening saves South Asian lives

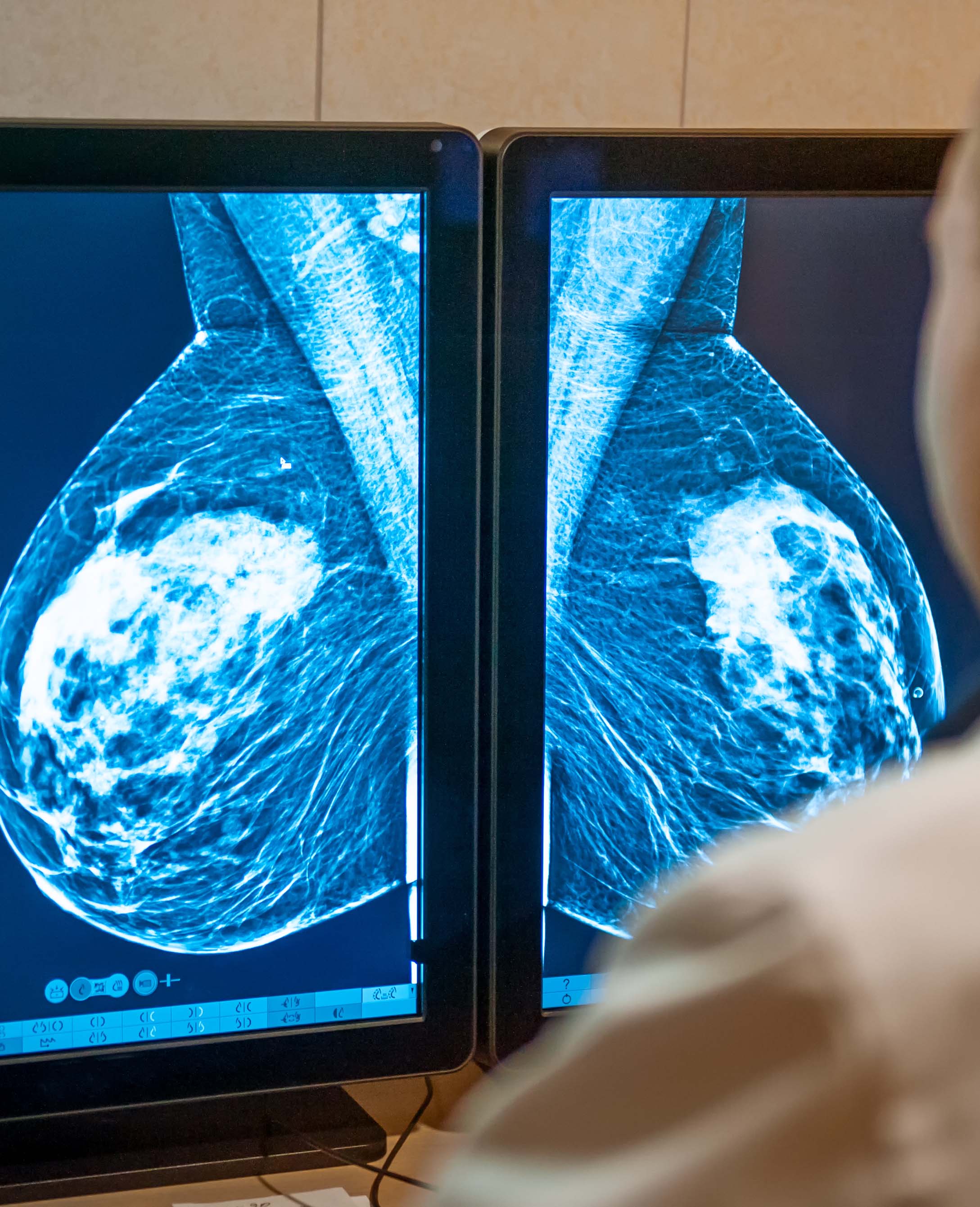

Age limits for routine breast cancer screening should be lowered to improve the life chances of South Asian women, according to research on patients at our hospitals.

Reducing the minimum age from 50 to 45 could double the chances of detecting breast cancer for women of Pakistani and Bangladeshi heritage in our communities.

A Barts Cancer Institute (BCI) study shows that South Asian women present earlier for breast cancer treatment with more aggressive symptoms and die younger.

Breast cancer is the most common cause of death among women globally, and mortality rates are higher among ethnic minorities.

North East London has some of the lowest survival rates in the country, which is why we are shortly opening a bespoke centre of excellence at St Bartholomew’s Hospital.

It also reinforces the significance of using our local patients in genetic research, which traditionally is dominated by participants from white European backgrounds.

Researchers from the BCI at Queen Mary University of London (QMUL) used data from over 7,000 breast cancer patients, of whom a third came from Barts Health hospitals or our partners in the east London Genes and Health project.

This meant the chosen cohort reflected the racial disparity of our population, though the authors also noted their findings may reflect higher deprivation levels, too.

They concluded that ethnically-adapted screening windows would be more equitable, with detection rates of 70% for South Asian women if the age was lowered to 45, and 64% for Black women if the age was lowered to 47.

Findings from the Genes and Health element of the study suggested detection rates among women of Pakistani and Bangladeshi heritage would improve from 24% to 59% (although the sample size was relatively small ).

Prof Louise Jones, the lead researcher, consultant in histopathology and professor of breast pathology, said: “At Barts Health and QMUL we are committed to equity of care for our diverse populations. Our research programme aims to understand differences in breast cancer among different ethnic groups that could impact how we test and treat our people.”

The study was funded through the National Institute for Health Research’s Barts Biomedical Research Centre.